Psychedelics may improve mental health by getting inside nerve cells

Psychedelics go beneath the cell surface to unleash their potentially therapeutic effects.

These drugs are showing promise in clinical trials as treatments for mental health disorders (SN: 12/3/21). Now, scientists might know why. These substances can get inside nerve cells in the cortex — the brain region important for consciousness — and tell the neurons to grow, researchers report in the Feb. 17 Science.

Several mental health conditions, including depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, are tied to chronic stress, which degrades neurons in the cortex over time. Scientists have long thought that repairing the cells could provide therapeutic benefits, like lowered anxiety and improved mood.

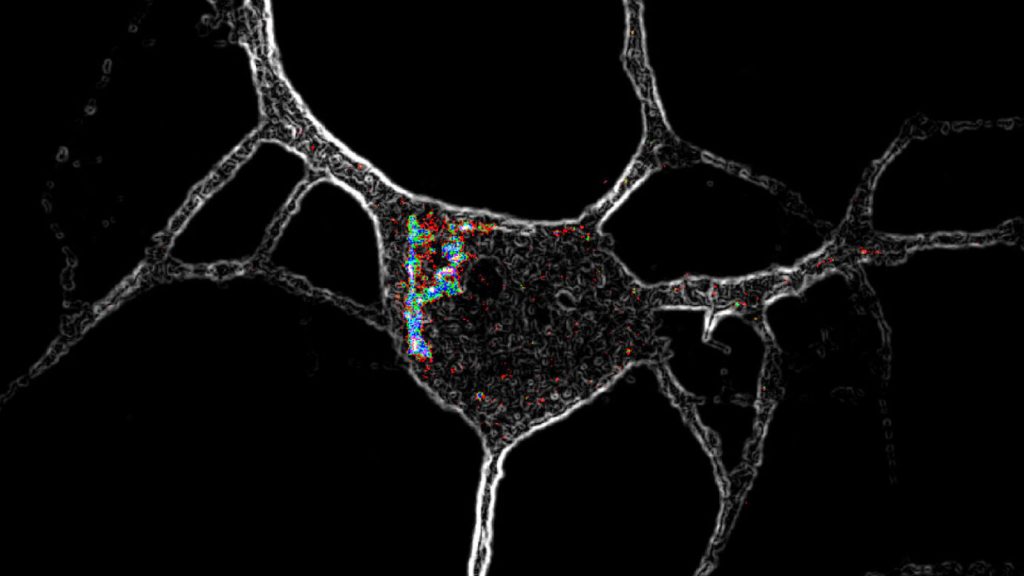

Psychedelics — including psilocin, which comes from magic mushrooms, and LSD — do that repairing by promoting the growth of nerve cell branches that receive information, called dendrites (SN: 11/17/20). The behavior might explain the drugs’ positive outcomes in research. But how they trigger cell growth was a mystery.

It was already known that, in cortical neurons, psychedelics activate a certain protein that receives signals and gives instructions to cells. This protein, called the 5-HT2A receptor, is also stimulated by serotonin, a chemical made by the body and implicated in mood. But a study in 2018 determined that serotonin doesn’t make these neurons grow. That finding “was really leaving us scratching our heads,” says chemical neuroscientist David Olson, director of the Institute for Psychedelics and Neurotherapeutics at the University of California, Davis.

To figure out why these two types of chemicals affect neurons differently, Olson and colleagues tweaked some substances to change how well they activated the receptor. But those better equipped to turn it on didn’t make neurons grow. Instead, the team noticed that “greasy” substances, like LSD, that easily pass through cells’ fatty outer layers resulted in neurons branching out.

Polar chemicals such as serotonin, which have unevenly distributed electrical charges and therefore can’t get into cells, didn’t induce growth. Further experiments showed that most cortical neurons’ 5-HT2A receptors are located inside the cell, not at the surface where scientists have mainly studied them.

But once serotonin gained access to the cortical neurons’ interior — via artificially added gateways in the cell surface — it too led to growth. It also induced antidepressant-like effects in mice. A day after receiving a surge in serotonin, animals whose brain cells contained unnatural entry points didn’t give up as quickly as normal mice when forced to swim. In this test, the longer the mice tread water, the more effective an antidepressant is predicted to be, showing that inside access to 5-HT2A receptors is key for possible therapeutic effects.

“It seems to overturn a lot about what we think should be true about how these drugs work,” says neuroscientist Alex Kwan of Cornell University, who was not involved in the study. “Everybody, including myself, thought that [psychedelics] act on receptors that are on the cell surface.”

That’s where most receptors that function like 5-HT2A are found, says biochemist Javier González-Maeso of the Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, who was also not involved in the work.

Because serotonin can’t reach 5-HT2A receptors inside typical cortical neurons, Olson proposes that the receptors might respond to a different chemical made by the body. “If it’s there, it must have some kind of role,” he says. DMT, for example, is a naturally occurring psychedelic made by plants and animals, including humans, and can reach a cell’s interior.

Kwan disagrees. “It’s interesting that psychedelics can act on them, but I don’t know if the brain necessarily needs to use them when performing its normal function.” Instead, he suggests that the internal receptors might be a reserve pool, ready to replace those that get degraded on the cell surface.

Either way, understanding the cellular mechanisms behind psychedelics’ potential therapeutic effects could help scientists develop safer and more effective treatments for mental health disorders.

“Ultimately, I hope this leads to better medicines,” Olson says.